When Covid descended like a plague of locusts on our country back in March 2020, parents got involved in schools. Parents showed up at Board of Education meetings, many for the first time, to tell their elected officials what they were doing wrong. Some wanted more HEPA filters and masks; others wanted less. Some wanted more hybrid education; others wanted less. People had many strong opinions, because that’s what happens when parents feel that their children’s well-being is at-risk.

Democracy is a contagious habit. Once you give people a taste for participation, they want to keep talking. And that’s a good thing. All these parents, who got a taste for local government and participation during the pandemic, want to continue to steer decision-making and to make sure that the other power players put the interests of kids front and center. What’s a good way to propel that energy in a positive direction?

One idea for parents is to focus on the huge disruption to reading education among the little kids that happened over the past two years.

Last week, Dana Goldstein, one of the education reporters at the New York Times, reported that a series of new studies showed that 1/3 of all children in the youngest grades are struggling with reading — a huge jump since 2020. Other facts from her article:

In the Boston region, 60 percent of students at some high-poverty schools have been identified as at high risk for reading problems — twice the number of students as before the pandemic.

Every child has fallen behind, but the biggest drops happened among black and Latino children, students who don’t speak English as a first language, and students with disabilities.

Students, who don’t have a good foundation at an early age, never catch up and end up with long term social issues. “Poor readers are more likely to drop out of high school, earn less money as adults and become involved in the criminal justice system.”

Students did not get enough stimulation during the school shutdowns, and it’s have a huge impact on learning, particularly in speech and reading.

Even though schools are now open, they don’t have enough special education teachers and reading specialists to cope with the huge needs.

Experts have been calling attention to the upcoming reading crisis for a while. The Hechinger Report, an excellent online education publication, published a piece last November about the reading lag among first graders, due to the pandemic. Some key points from this article:

“Research shows if children are struggling to read at the end of first grade, they are likely to still be struggling as fourth graders. And in many states with third grade reading “gates” in place, students could be at risk of getting held back if they haven’t caught up within a few years.”

40 percent — The number of first grade students “well below grade level” in reading in 2020, compared with 27 percent in 2019, according to Amplify Education Inc.

The article does a deep dive into one classroom. Really worth a read.

What should parent-activists do about this problem? Well, they should make sure that their school district is doubling up their efforts in the younger grades. Tax money is finite; school leaders can’t fund everything equally. So, parents should make sure that the school puts money where it will matter most. Perhaps the football team doesn’t need a new field this year. Perhaps the school doesn’t need 20 AP classes, some with only a handful of students. With those extra resources, administrators should hire after-school tutors and maybe even double up on reading classes during the day.

Education Links of the Week

Alabama schools investing $434M in COVID aid on athletic complexes, weight rooms, ‘zen rooms’

Effects of School Closures Resulting From COVID-19 in Autistic and Neurotypical Children

This is from “The Great Leap” - my newsletter about the transition from high school to adulthood for teens with autism.

The Dispatch is a center-right general politics newsletter. This piece from Fred Hess.

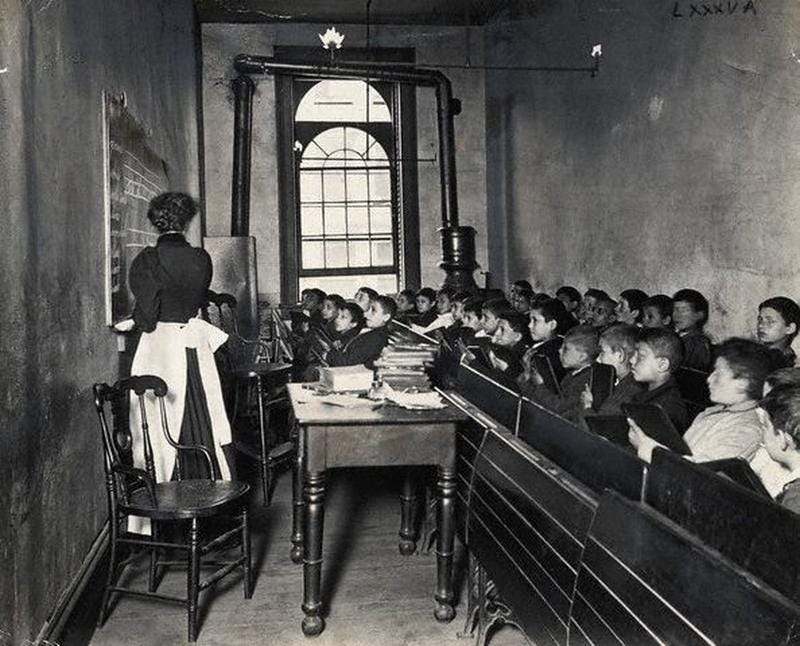

Pictures: Source