During the pandemic, parents often complained to me that journalism was biased and wasn’t covering the real damage done to their kids during school shutdowns. They pointed to the dawn to dusk coverage on CNN of the dangers that existed in schools, but little discussion about learning lag, speech delays, mental health issues and the host of other social ills caused by remote education. They scanned the front page of the New York Times looking for news on a topic that concerned them the most — their kids — and saw nothing.

Many parents believed that the silence from the major media sources was proof of a conspiracy, an unholy alliance between the media and the teachers’ unions and Democratic elite. As usual, reality is a lot more complicated. So, let’s break it down.

Journalists are not BFFs with teachers’ union leaders. However, they do need them for their stories. Almost every education story has to feature a teacher, administrators, and a view from the classroom. The teachers’ unions are the most powerful organized group in education politics, so any quality article should include a quote from them on the topic. If a journalist makes enemies with this powerful group, then they cannot do their jobs. A super negative piece on the unions could be a career killer. Like any niche journalism, education journalism enjoys a symbiotic relationship with their subjects, and there must be a delicate balance in that relationship.

Many education journalists are also parents. And parents were overwhelmed with parenting responsibilities during the pandemic. I wrote an op-ed in the newsletter for the Education Writers Association about my own obstacles to doing my job during the pandemic. So, the best writers in the field were sidelined, and the education beat was picked up by others in the newsroom with less experience.

The problems hitting kids may have been ignored by major news sources, like CNN, but they were given attention by some great education-specific websites and news sources. (Remember: There is no monolithic media empire.) If schools are your favorite topic, I recommend bookmarking The 74, The Hechinger Report, and Chalkbeat. I signed up for their newsletters and follow them on Twitter, so I get my education news mainlined into my veins every morning.

I also want to recommend Alexander Russo’s The Grade. It’s a newsletter for education journalists with insider gossip about job changes and best articles of the week, but Russo also keeps journalists accountable. He’s not afraid to point out when journalists can do better. His picks for the best education articles of the week are always useful, not just for other journalists. Throughout the pandemic, Russo was frequently amplified the views of parents on Twitter.

So, there are a diversity of views and opinions about schools within the journalism community. Read the good stuff; follow, link, forward, and amplify them.

Then there were problems with reporting school issues that no-one could envision. Nobody thought the pandemic would go on for so long and that school shutdowns would have such devastating impacts. Editors like articles that are “evergreen” and can be run over and over. Just as television shows never put their characters in masks, newspaper and magazine editors didn’t want to commit to articles that would have a short shelf life. So, they may have chosen to actually delete information about remote education in longer stories.

Not everyone experienced the pandemic the same way. As a parent of a special needs kids in a low-risk community, I had one perspective. Another parent with a honors student kid with a host of private tutors and private basketball camp experienced a different pandemic. And a single parent in Newark, who was completely overwhelmed with issues much bigger than their kids’ math scores, experienced yet another pandemic. All three experiences are valid and real, but which one experience should a journalist cover in 800 words? It’s not easy to make those decisions, so don’t throw stones.

Lastly, news stories about schools are — let’s admit it — formulaic. Before the pandemic, the education stories were always the last one on the news or in the back of the paper. They had to be heart warming tales about resilient kids with their help of their plucky teachers who overcome all odds and get accepted to the Ivy League college of their choice. Or they might be some groundbreaking new robot that will teach autistic kids to talk. Or a new study that would “revolutionize” the way that we teach kids.

Nobody wants to read the real story about schools. Want to know what percentage of students are reading proficiently in the United States? 34 percent. It’s sad. The solutions are expensive. And most media consumers are the folks whose kids are doing just fine and would prefer to keep the blinders up, so news editors give the consumers the happy news and sit on the depressing stories. This isn’t a pandemic-specific issue; this is an “always” issue.

In short, you may not have gotten the full picture from the media about what was happening to kids during school shutdowns for a whole lot of reasons. Those reasons were less about politics, and more about practicalities. The good news is that many of these problems can be fixed by supporting the high quality education-specific outlets that are supported independently by big foundations. Those outlets have greater flexibility and more expertise than some of the bigger media outlets.

We get the journalism that we deserve. That’s not just for education policy, but for everything. Be picky and be demanding, and we’ll get better media.

LINKS

Opinion, NYT: Why are we letting Republicans win the school wars?

Is the middle-class family in trouble?

Low college enrollments is going to be a massive issue going forward.

And a related piece from me at The Atlantic.

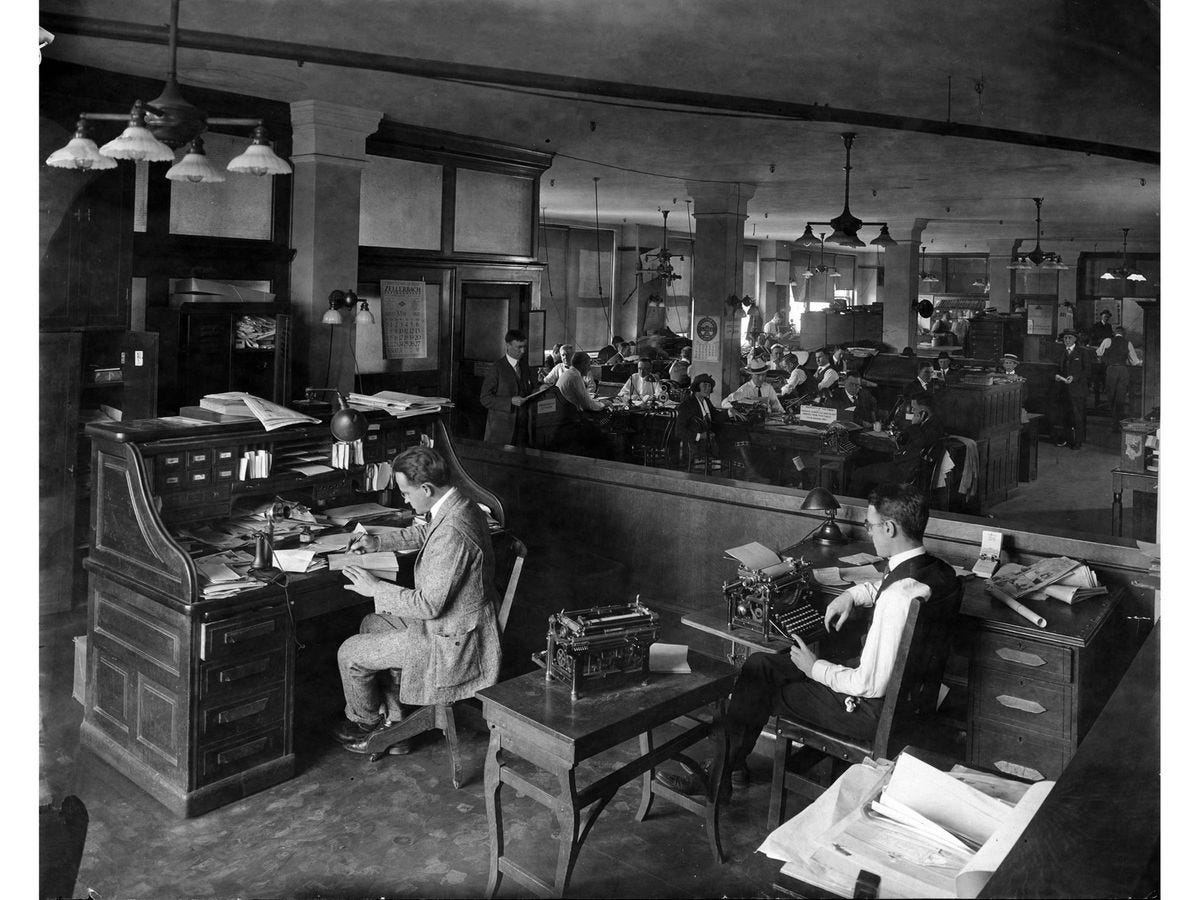

Picture: source